Summary and Investment Conclusion

Capital markets can see the characteristics of, and thus place reasonable values on, drug products that are on-market, in registration, or in very late (phase III) development (which we call ‘tangible’). Conversely the market cannot see the characteristics of earlier-stage developmental products, and so arguably cannot accurately value pre-phase III assets (which we call ‘intangible’)

Even though companies do not publish comprehensive details of early (‘intangible’) pipelines, they do file patents. Using patents, patent applications and related metrics, we’ve developed comparative indices of the apparent ‘amounts of innovation’ produced by each major pharmaceutical company

We solve for the value of mid- to early-stage ‘intangible’ pipelines by subtracting the value of tangible products from companies’ enterprise values (EVs). We then compare the apparent market value of intangibles to the apparent level of innovation in each company’s mid- to early-stage ‘intangible’ pipeline

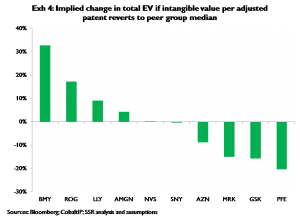

Because intangible product values are a reasonably large percentage of large cap drug companies’ total EV’s; and, because intangible valuations are inherently inaccurate, we believe the relative performance of large cap drug companies over the middle-term (+/- 4 years) is heavily influenced by changes in the relative values of intangibles. At the whole company levels, BMY and Roche appear more than 10 percent undervalued versus peers; PFE, GSK, and MRK appear more than 10 percent overvalued versus peers

We also offer two contemporary company-specific estimates of relative R&D productivity: 1) dollars of R&D spent per adjusted (for apparent level of innovation) patent; and 2) the relative rates at which each company is either generating or losing adjusted patents. BMY, SNY, and Roche appear to produce substantially more innovation per R&D dollar than peers; LLY substantially less. BMY, SNY, and AZN appear to have much better ratios of new adjusted patents being won to old adjusted patents being lost than peers; LLY’s ratio is much worse than peers’

Adjusted Patents as an Index of Innovation

Companies’ disclosures of pre-phase III research pipelines is selective and incomplete; thus typical information sources offer no immediately apparent way of assigning values to mid- / early-stage pipelines

However companies seek patent protection for developmental assets much earlier in the development process than they make scientific, academic, or investor-focused disclosures about these same assets. Because issued patents (and patent applications > 18 months old) are publicly available, patent databases offer a useful (and under-utilized) means of assigning values to companies’ pre-phase III pipelines

In and of themselves, patents and patent applications have limited usefulness; because the value of patents varies greatly, simple patent counts aren’t terribly useful. Patent citations carry far more signal value. After a patent is issued, subsequent applications that make claims in a similar ‘space’ have to reference (or ‘cite’) the earlier patent if the claims of the earlier patent represent a limit on the scope of claims in the subsequent patent. Thus ‘forward citations[1]’ are a useful measure of a patent’s value – the more forward cites a patent accumulates, the more value it likely has as compared to other less-cited patents

We’ve developed a ‘vintage and citation adjusted’ index[2] of biomedical patents held by publicly traded innovators. For each company, we divide adjusted patents into ‘tangible’ and ‘intangible’ groupings – ‘tangible’ adjusted patents are those that can be tied to products that are either approved, filed for approval, or in phase III human testing; ‘intangible’ adjusted patents are the remainder. Because companies need to seek patent protection early in the development process, and because (we believe) companies’ patenting strategies for developmental compounds are quite similar, each company’s portfolio of intangible adjusted patents is a useful benchmark of the relative value of its mid- / early-stage pipeline

The Relationship between Intangible Valuations and Intangible Patent Portfolios

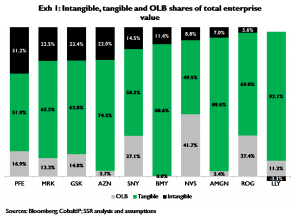

We solve for the market value of each company’s intangible future products by first establishing the present value of its tangible current products, and subtracting this tangible present value from total EV. We use a highly standardized framework for calculating tangible present values; where possible the framework makes use of historic evidence, particularly as it relates to projecting sales and profits beyond periods of reported results and/or credible consensus forecasts. The framework is applied at the product level, i.e. companies’ tangible values are the sum of the calculated tangible values for each product that the company reports as a separate line item. For companies with significant non-pharma businesses, these businesses’ contribution to total EV is estimated using sales multiples for pure-play or ‘near-pure-play’ comparables. The percentage of each company’s EV attributable to either tangible or intangible product portfolios is provided in Exhibit 1

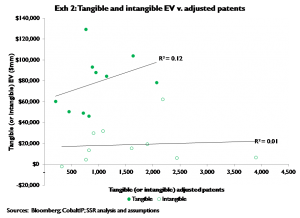

We then compare tangible product valuations to the portfolio of adjusted patents that reference on- market, filed, or phase III products by company, and intangible valuations to the remainder of the adjusted patent portfolio – i.e. the intangible adjusted patents. Exhibit 2 shows the general pattern – obviously ‘tangible’ dollars of EV per ‘tangible adjusted patent’ are greater than ‘intangible’ dollars of EV per ‘intangible adjusted patent’, since intangible assets face considerable time and risk before they reach market. However more important to our general thesis is that tangible adjusted patent valuations occupy a more narrow range than intangible adjusted patent valuations[3]. I.e., adjusted patents for products that reach market (or at least phase III) have more consistent values than adjusted patents for products that are pre-phase III. This implies that as middle- to early-stage pipelines mature (i.e. become ‘tangible’), that intangible valuations per intangible adjusted patent should gather more closely around the median – i.e. that companies with relatively low intangible values per intangible adjusted patent should outperform their peers, and vice versa

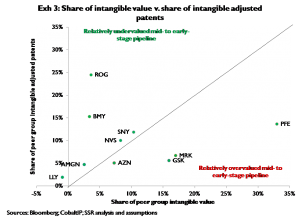

Exhibit 3 compares each company’s share of total peer group intangible adjusted patents to its share of total intangible value for that same peer group. On this basis Roche and BMY appear undervalued; PFE, MRK, and GSK appear overvalued. Exhibit 4 shows the change in each company’s total EV on the assumption that the per-adjusted patent value of its intangible adjusted patents reverts to the peer group median. Assuming typical portfolio structures (specifically typical mixes of large and small molecule projects in the ‘intangible’ phases, i.e. preclinical, phase I, and phase II), misvaluation of intangibles should be largely resolved within a four-year period[4], all else equal[5]

Due Diligence

In theory, the variance in intangible values could be a conscious market wager on the relative quality of innovations produced. Considering only patents with citations, and adjusting for the portfolio-weighted vintage[6] of patents, we index the relative rates at which various companies’ cited intangible patents accumulate citations. Companies with values higher than 1 have intangible patents that tend to accumulate citations more rapidly than peers’ and vice versa. Correspondingly, the apparent level of innovation represented by each adjusted patent in the intangibles portfolio of a company with index values higher than 1 arguably is above average, and vice versa. The cited patents in BMY and Roche’s intangible patent portfolios accumulate cites more rapidly than the average; this argues that BMY and Roche’s intangible cites are actually worth more than average, even though they are undervalued relative to the average. Conversely PFE’s intangible cited patents accumulate citations at about the average rate, and MRK and GSK’s intangible cited patents accumulate citations more slowly than average. This implies that PFE’s intangible adjusted patents have average values despite having an above average valuation; MRK and GSK’s intangible adjusted patents may have below average ‘true’ values despite also being valued above the peer group average

Also, the variance in intangibles values may reflect a conscious bet relating to how much time is left on any given company’s more innovative patents. Accordingly we control for the percentage of intangible citations that are in patents likely to expire in the near term – because even if a patent has accumulated cites at a rapid rate, that patent is far less likely to underpin a substantial amount of present value if the patent expires before the related product can reach the market. Here we simply calculate the percentage of intangible adjusted patents with >= 5 years of remaining patent life

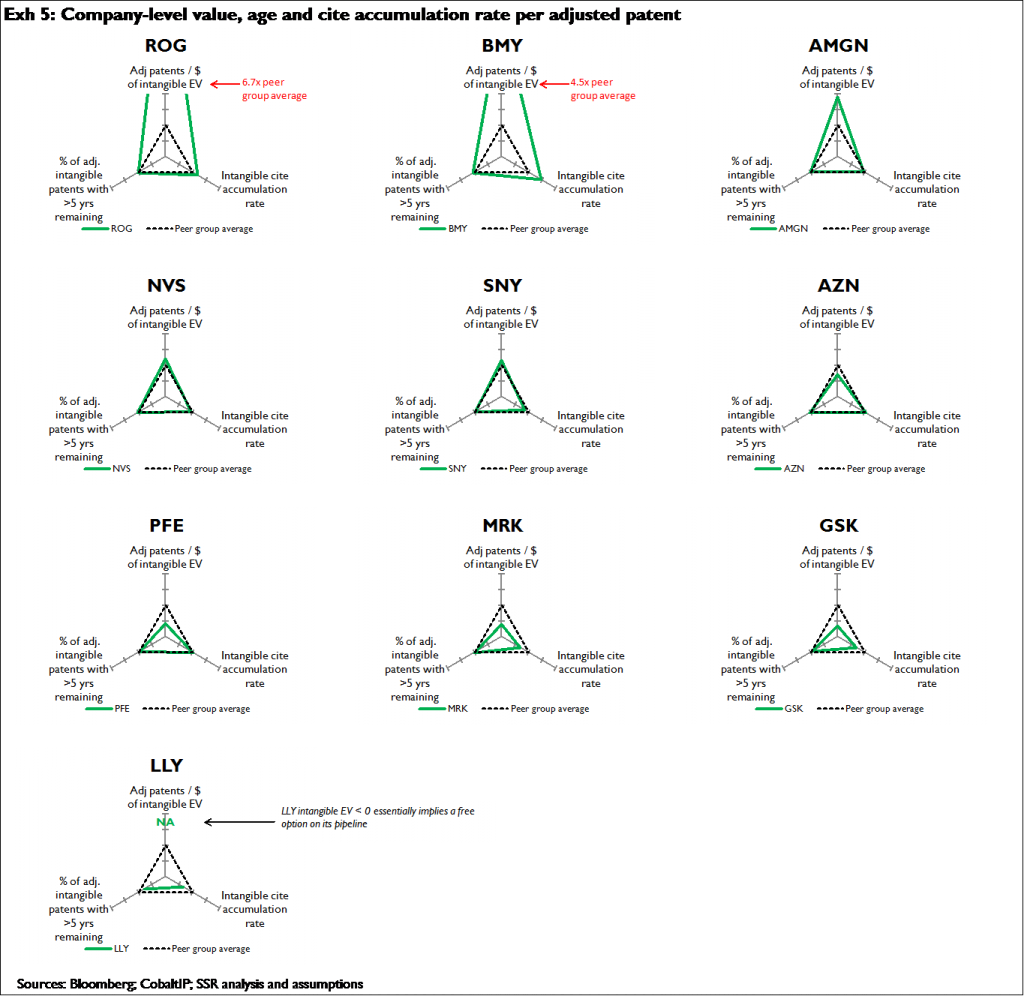

Exhibit 5 compiles the three related values: 1) adjusted intangible patents / intangible dollar of EV; 2) relative rate of cite accumulation for cited intangible patents; and 3) the percentage of adjusted intangible patents with >= 5 years of remaining patent life. In all cases higher numbers signify greater value

BMY and Roche appear to offer the most undervalued intangible pipelines; both offer more adjusted patents per dollar of intangible EV, and both companies’ intangible adjusted patents appear to be of greater than average value, in that these patents are accumulating citations more rapidly than peers. MRK and GSK appear to offer the least intangible value; each offers substantially fewer intangible adjusted patents per dollar of intangible EV than peers, and the rate of citation accumulation for both companies’ intangible adjusted patents is below par. PFE’s adjusted intangible patents appear overvalued relative to peers; however unlike MRK and GSK, PFE’ intangible adjusted patents are accumulating citations at the par rate. LLY is a special case; the company has relatively few intangible adjusted patents, but its intangibles value is negative, because our estimate of the present value of the existing businesses slightly exceeds the company’s current EV. Thus in essence LLY offers a free option on its intangibles portfolio; however the intangibles portfolio is relatively small, and its low rate of cite accumulation indicates the intangibles may have relatively low ‘true’ values

Productivity

Patent data offer some level of insight into relative levels of R&D productivity on a company by company basis. R&D productivity should be considered at least somewhat independently of whether we view companies as under- or over-valued based on dollars of intangible EV per intangible adjusted patent. For example, if Company X appears undervalued because of a very low ratio of intangible EV to intangible adjusted patents, we might prefer to own it even if it spent more R&D dollars to produce its undervalued adjusted patent portfolio

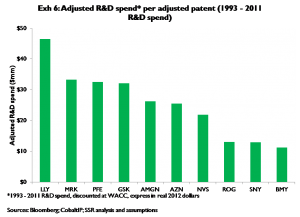

We measure relative R&D productivity two ways. First and most simply, we divide each company’s total (i.e. both tangible and intangible) adjusted patents by the company’s trailing (1993 – 2011) R&D spend. Companies that spend more R&D dollars per adjusted patent than peers arguably are less productive, and vice versa. Results are in Exhibit 6; on this basis BMY, SNY, and Roche have higher than average levels of R&D productivity; LLY appears to be the least productive by some margin

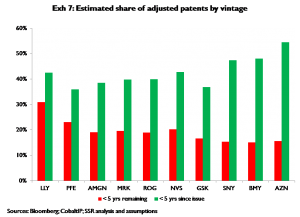

Second, we consider the relative rates at which adjusted patents (both tangible and intangible) are being formed, and the rates at which adjusted patents are expiring; specifically we compare the percentage of a company’s adjusted patent portfolio that has been issued in the last five years to the percentage that is likely to expire in the next five years. On this basis SNY, BMY, and AZN appear have the most beneficial balance of new innovation v. expiry of older innovations; LLY appears to have the least beneficial balance (Exhibit 7)

[1] Citations by later-issued patents (or applications) that reference earlier-issued patents (or earlier filed but now public applications)

[2] Forward cites are not created equal – the older a patent, the more time it has to accumulate cites, and vice versa. Accordingly a younger patent with the same number of cites as an older patent is presumably more innovative – since the younger patent accumulated cites at a faster rate. Patent ‘vintage’ also matters; patents issued in certain years accumulate cites more rapidly than patents in other years. Our index controls for both effects

[3] We recognize that the absolute r-squared values are quite low; however the difference in the relative r-squared values is significant. Also, we would emphasize that the variance in value per adjusted patent for the tangible on-market (or near-market) products must be driven in large part by the highly visible differences in products themselves – differences which the capital markets can plainly see, and thus can value. In contrast, the differences in the relevant features – and thus true values — of the intangible middle- to early-phase development projects is largely hidden from the market; accordingly the noise in per patent adjusted values for intangible portfolios presumably is mainly that — noise

[4] More specifically, about 40 percent of the (time and risk adjusted) present value of pre-phase III (i.e. intangible) projects can be found in phase II; and, the average duration of phase II is roughly 28 months, implying that 40 percent of intangibles misvaluations should resolve within this 28 months (i.e. it takes 28 months for phase II intangible projects to become phase III tangible projects). About 37 percent of intangibles present value is in phase I; these projects are on average roughly 45 months from reaching phase III (i.e. from becoming ‘tangible’). The remaining 23 percent of intangibles present value is in discovery / preclinical; on a present value weighted basis these projects are on average nearly 10 years from becoming tangible (phase III) assets. Across all intangible phases, the present-value weighted time until reaching phase III is roughly 53 months; however the majority of present value (phases I and II) reach ‘tangible’ phase III status within 45 months, thus our conclusion that intangibles misvaluations should largely resolve over a four-year period

[5] Intangibles misvaluations in and of themselves are not a complete foundation for a buy or sell recommendation; obviously more traditional ‘tangibles’ values also have to be considered

[6] See footnote 2: the year a patent is issued affects the rate at which the patent accumulates citations