Premise and rationale behind the ‘Hidden Pipeline’ valuation method

Share prices of drug and biotech stocks arguably can be broken down into two major components: the capital markets’ estimates of the value of assets that are well characterized (i.e. on-market, filed, and late-stage developmental projects), plus the markets’ estimates of the value of assets about which relatively little is known (i.e. pre-phase III projects). For simplicity, we refer to early, pre-phase III developmental projects collectively as the ‘Hidden Pipeline’

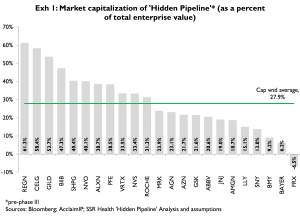

To estimate the values of hidden pipelines as a percentage of share prices, we subtract from each company’s enterprise value an estimate of the present value of everything else – marketed products, products filed for regulatory approval, products in phase III development, and all non-pharma lines of business. On average, hidden pipelines account for more than a quarter of share prices, and the percentage of share price explained by hidden pipelines ranges from a low of (less than) zero, to a high of more than 50 percent (Exhibit 1)

In theory, if the capital markets had equal amounts and qualities of information on these companies’ hidden and non-hidden operations, we would expect that knowing what’s in the hidden pipeline would take us roughly one-quarter of the way to explaining relative share price movements among these companies over time. However because the markets have substantially more information regarding non-hidden operations than they have regarding hidden pipelines, the valuations of hidden pipelines are much rougher guesses. By extension, this implies that the hidden pipeline valuations are inherently far more volatile than the valuations of non-hidden operations, and by further extension that hidden pipelines explain substantially more than one-quarter of relative performance among these stocks

Price versus Value …

Having solved for the market capitalization of a company’s hidden pipeline, the question becomes whether or not the assigned market value closely reflects the hidden pipeline’s true economic value. To estimate pipelines’ true (relative) economic values, we rely heavily on patent data which, unlike traditional channels of disclosure, offer a reasonably consistent and complete[1] picture of companies’ hidden pipelines

After assigning all active[2] patents to their corresponding parent companies, we take three key additional steps: 1) each patent is quality weighted[3]; 2) patents are segregated into those that correspond to either known (e.g. marketed, filed, or late stage projects) or hidden (pre-phase III) products / projects; and 3) each ‘hidden’ patent is assigned to disease, mechanism, and/or physical (chemical / biochemical characterization) categories[4]. The result is a company-by-company database that characterizes the sizes (numbers of quality-adjusted patents) and relative values (quality-adjusted patents, weighted further by the relative economic values of the disease areas in which the company conducts research) of the analyzed companies’ hidden pipelines

To determine which companies’ pipelines appear relatively over- or undervalued, we simply compare the market capitalization (price) of each company’s hidden pipeline to the apparent (relative) economic value of that company’s hidden pipeline

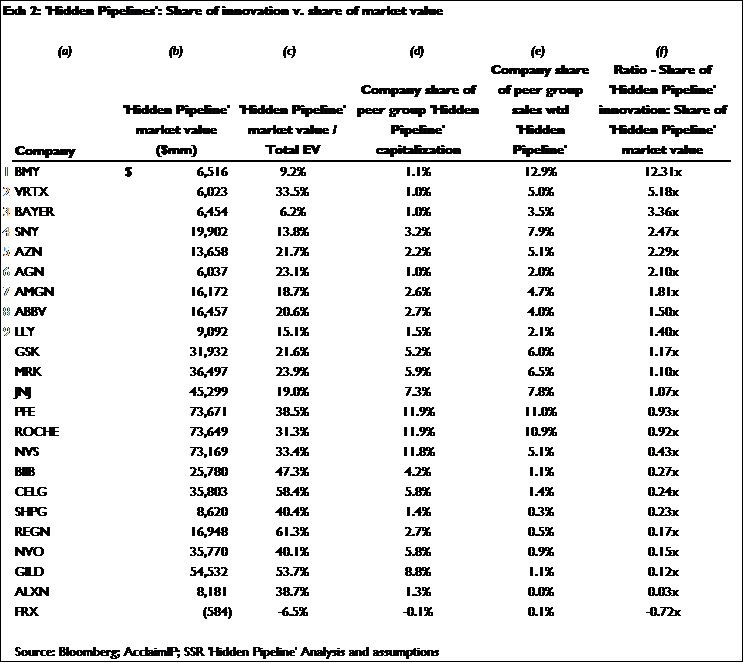

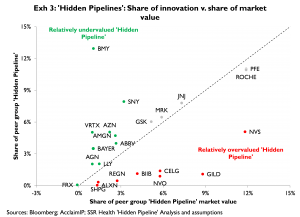

Exhibits 2 and 3 summarize the results. In Exhibit 2, column (b) provides our estimate of the market capitalization of the hidden pipeline[5], and for reference column (c) shows hidden pipeline capitalization as a percent of total enterprise value. Column (d) gives each company’s hidden pipeline value as a percent of the total hidden pipeline value for all companies. Using BMY as an example, BMY’s $6.5B hidden pipeline capitalization is about 1 percent of the $620B combined capitalization for all 23 companies’ hidden pipelines’. In column (e) we express the quality- and sales-weighted amount of innovation in each company’s hidden pipeline, as a percent of the total quality- and sales-weighted innovation in all 23 companies’ hidden pipelines. Column (f) is the ratio of columns e & d; i.e. column (f) is the share of peer group innovation in a given company’s hidden pipeline, divided by that company’s share of total peer group hidden pipeline market value. Companies with much larger shares of innovation than of market value (e.g. BMY) have hidden pipelines that are apparently undervalued, and vice versa[6]. Exhibit 3 depicts the data in Exhibit 2 graphically, comparing each company’s share of the peer group’s quality- and sales-adjusted hidden pipeline (y-axis), to its share of the total peer group’s hidden pipeline capitalization (x-axis). Companies that depart significantly from the 45 degree ‘normal’ have hidden pipelines that are apparently under- (above the normal line) or overvalued (below the normal line)

BMY, VRTX, Bayer, AGN, SNY and AZN have hidden pipelines that appear undervalued[7]; FRX, ALXN, NVO, GILD, REGN, SHPG, CELG, BIIB, and NVS have hidden pipelines that appear overvalued[8]

Implied performance, and actual performance to date

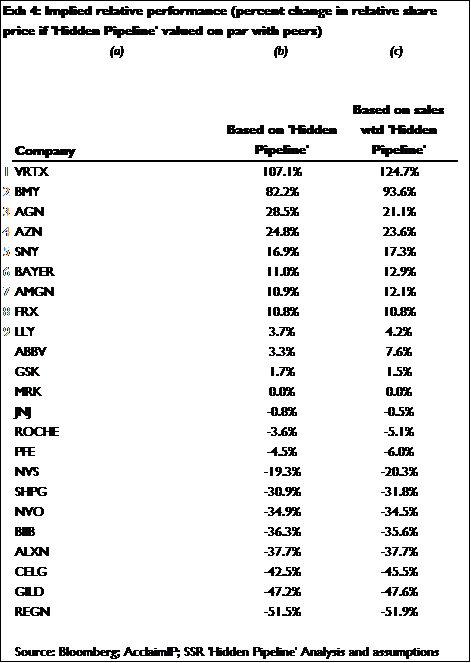

Implied performance is simply the percentage change in relative share price that would bring a given company’s hidden pipeline valuation to par. Fundamentally, the idea is that a given hidden pipeline, adjusted for the sales potential reflected in its therapeutic area mix and the quality-adjusted volume of total innovation, should have the same or nearly the same economic value[9] as an ‘average’ pipeline with the same therapeutic area mix, and quality-adjusted volume of innovation

Results are provided in Exhibit 4, both with and without sales weighting of hidden pipeline values. Using BMY as an example, based only on the amount and quality of innovation in BMY’s hidden pipeline, and assuming only that this amount and quality of innovation ultimately is valued at par with other ‘Hidden Pipelines’ of comparable amounts and quality of innovation, we would expect BMY to outperform its peers by roughly 82 percent. If in addition, we adjust our estimate of the value of BMY’s hidden pipeline to account for the mix of therapeutic areas BMY is pursuing, we would expect BMY to outperform its peers by roughly 94 percent. Conversely if NVS’ hidden pipeline were valued at par, we would expect NVS to underperform by roughly 19 percent (ignoring therapeutic area mix) or, adjusting for the therapeutic area mix of NVS’ pipeline we would expect underperformance v. peers of roughly 20 percent

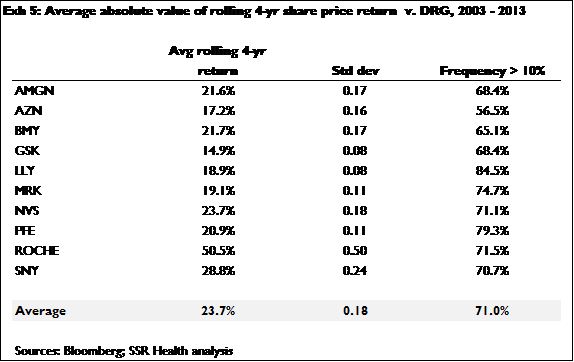

Because of the time necessary for ‘Hidden Pipelines’ to mature into tangible projects about which the market has sufficient information to efficiently assign values, we believe the misvaluations associated with companies’ ‘Hidden Pipelines’ should resolve gradually over roughly 4 years. We note that the average implied relative performance for the large-cap pharma names in Exhibit 4 is roughly 16 percent, and that this implied relative performance is comparable to the 24 percent average relative (rolling 4-yr) performance of these names over the last decade (Exhibit 5). This is consistent with, though does not prove, our assertion that hidden pipeline misvaluations have the potential to explain a very large percentage of the relative share price movements across the larger drug and biotechnology names

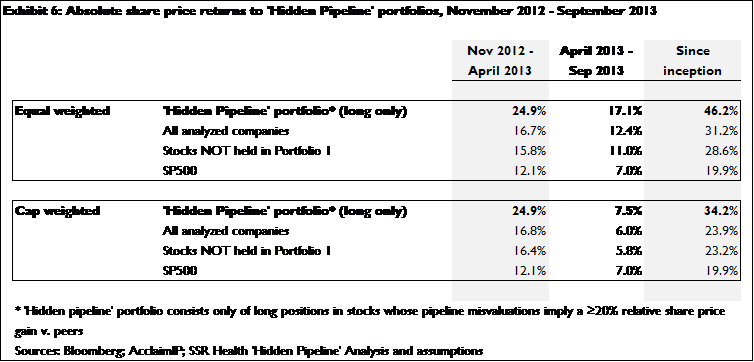

Exhibit 6 provides the actual relative performance of a drug / biotech portfolio whose stock selection is based entirely on hidden pipeline valuation (all names with ≥ 20 percent implied share price gain are held long). Performance figures are provided for the entire period since we first published the method (Nov 2012) and for each interval between updates. Since inception, returns to stocks chosen based on hidden pipeline valuations are roughly 1.45x peer group returns (1.48x equally weighted; 1.43x cap weighted)

R&D Productivity

Independent of whether companies’ pipelines appear over- or undervalued, by comparing the amount of innovation generated to the amount of R&D invested, we can evaluate (within limits) the apparent relative R&D productivity of each company

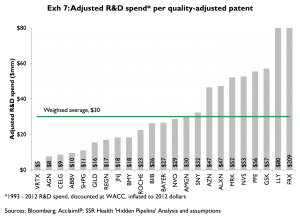

Exhibit 7 is a simple and direct comparison of R&D spend to quality-adjusted innovation produced. The numerator is WACC- and time-adjusted R&D spending from 1993 – 2012; the denominator is the total amount (all patents, whether ‘hidden’ or tied to ‘tangible’ assets such as marketed, filed, and/or phase III projects) of quality-adjusted innovation reflected in each company’s entire portfolio of unexpired patents[10]. The output is R&D dollars spent per standardized, quality-adjusted ‘unit’ of innovation. Here we make no assertions regarding what a quality-adjusted unit of innovation is actually worth, other than to say a quality-adjusted unit of innovation at one firm should be worth roughly the same as at another firm[11], thus if one firm (e.g. LLY) spends on average $80M producing a quality-adjusted unit of innovation and another spends on average $18M (BMY), the latter appears far more productive than the former

Exhibit 7 gives some idea of the relative R&D productivity by firm over the past 20 years, but no sense of whether a given company is improving (or deteriorating) in terms of relative R&D productivity versus its peers. To establish whether a given company is gaining or losing relative R&D productivity, we consider three metrics: 1) the company’s share of industry R&D spending in a given year divided by its share of industry (quality-weighted) innovation reflected in patents granted that same year; 2) the company’s absolute R&D spend in a given year divided by the quality-adjusted number of patents granted to the company that year, as compared to the same ratio for the industry as a whole; and 3) the percentage of the company’s unexpired, quality-adjusted, hidden pipeline patents that fall into any of four age groups, as compared to the percentage of the industry’s unexpired, quality-adjusted, hidden pipeline patents falling into those same age groups

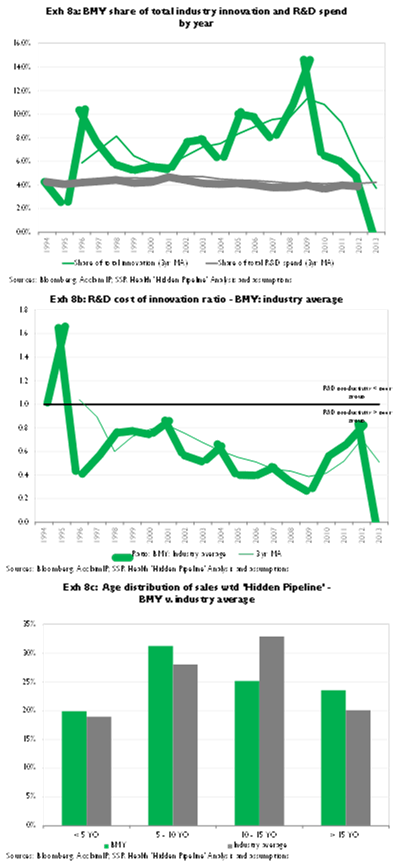

Exhibits 8a thru 8c provide each of these three metrics for BMY, and Appendix A provides each metric for each of the remaining 22 companies in the analysis

Exhibit 8a shows that BMY has consistently had a greater share of the industry’s quality-adjusted innovation (green line) than of R&D spend (grey dashed line), which implies that BMY has consistently shown greater R&D productivity across this period. We caution against over-interpreting a company’s share of innovation in either the earliest (e.g. 1994 – ’95) or latest (e.g. 2012 – ’13) years of the analysis. In both cases, the number of quality-adjusted patents available to evaluate can be quite small – the number of patents in the early years falls as a result of accumulating patent expirations, and the number of quality-adjusted patents is limited in the most recent years by the fact that patents issued in these years have not had sufficient time to accumulate citations, which heavily affects quality weighting. Also, we stress that the amount of R&D spent in a specific year isn’t tied directly to the amount of innovation reflected in patents granted in that same year. R&D spending tends to be dominated by development spending, which is on products whose patents would have been granted several years prior. To be meaningful, the comparison in Exhibit 8a has to be considered across multiple years

Exhibit 8b compares BMY’s R&D cost per quality-adjusted ‘unit’ of innovation to the industry’s overall R&D cost per quality-adjusted unit of innovation. Here again, the comparison involves R&D spend in a specific year with the quality-adjusted innovation reflected in patents granted that same year, so it’s necessary to consider the ratio across multiple years for it to be meaningful. Exhibit 8b shows that the amount BMY spends on R&D per unit of innovation has been consistently below the industry average, and that if anything BMY’s relative R&D productivity versus peers may actually be improving. As with Exhibit 8a, caution is necessary when considering the very early or very late years of the comparison, as the number of patents in the denominator is small in both cases (early-year patents are expiring, and later year patents have only begun to accumulate citations, thus quality-weights for these recent patents are noisy)

Finally, Exhibit 8c shows the age distribution of BMY’s active, quality-weighted, hidden pipeline patents, as compared to the average age distribution for the industry. BMY’s quality-weighted hidden pipeline portfolio is on average 0.05 years (18 days) older than the industry average; however the age distribution shows that BMY has significantly more younger (< 5 y.o. and 5-10 y.o.) quality-weighted hidden pipeline patents than peers, implying that BMY’s relative rate of innovation has accelerated versus peers

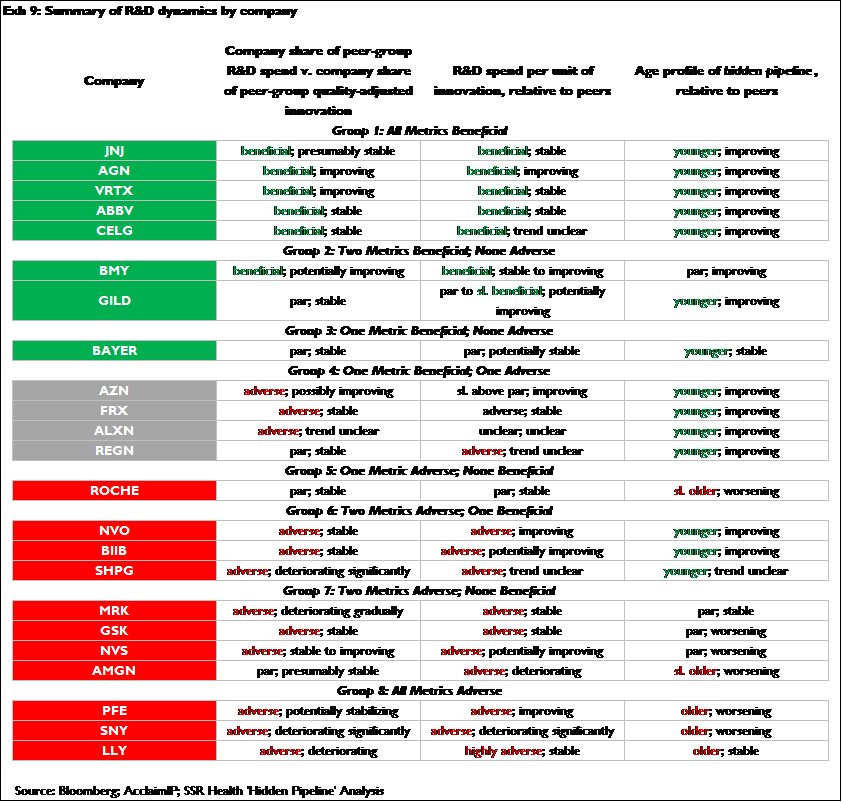

Each of these three comparisons is provided for the remaining 22 companies in the analysis in Appendix A; however in Exhibit 9, we summarize each of these three measures by company. Please see the appendices for detailed time series by company, and when comparing a company’s time series to our interpretation, please bear in mind that we largely ignore 2012 and 2013 data for the first two metrics for reasons explained above

So what’s in BMY’s ‘Hidden Pipeline’?

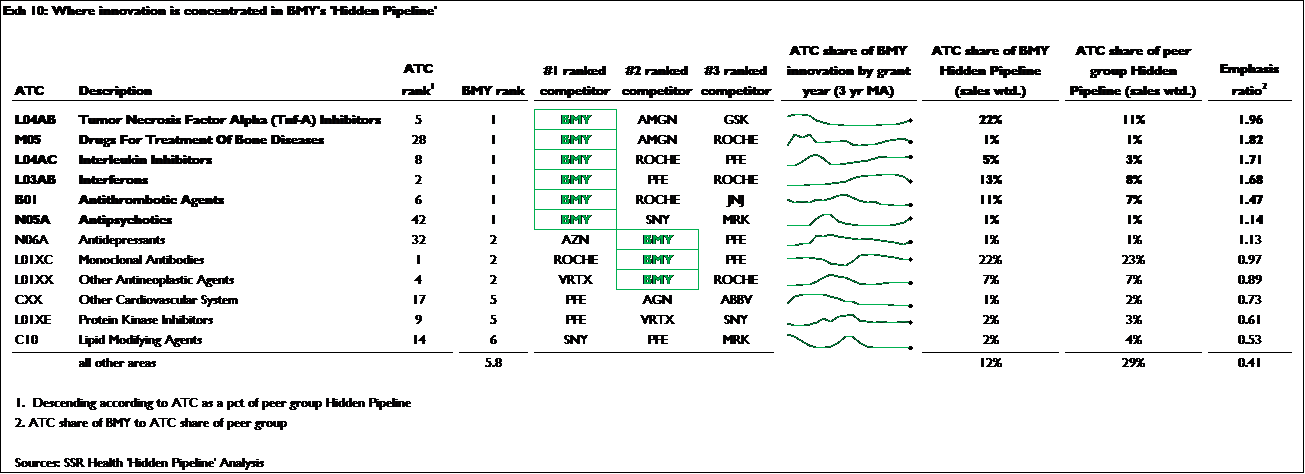

Our ‘Hidden Pipeline’ dataset sorts each company’s pre-phase III quality- (and optionally sales-) weighted patents into estimated WHO (World Health Organization) standard ATC (Anatomic / Therapeutic / Chemical) categories. This allows us to allocate the apparent innovative activity in BMY’s (or any other company’s) pipeline by research area (i.e. by ATC). Exhibit 10 ranks BMY’s hidden pipeline by ATC code, in descending order according to ‘emphasis ratio’ (far right column), which is a metric of how much more (or less) intently a given company is focused on a given research area as compared to its peers. Specifically, the emphasis ratio is a given ATC as a percent of quality-weighted innovation in the company’s hidden pipeline, as compared to that same ATC as a percent of the quality-adjusted innovation in the peer group pipeline

The 12 research areas (ATCs) for which BMY has an emphasis ratio of 0.5 or greater are listed in Exhibit 10. These areas represent 88 percent of the quality- and sales-weighted innovation in BMY’s hidden pipeline, as compared to 71 percent of the quality- and sales-weighted innovation in the peer group pipeline. For reference, in Exhibit 10 we also show the ATC’s rank for the total group and for BMY; the top three companies in each ATC; and, a sparkline graphic depicting the share of BMY’s hidden pipeline represented by that ATC over the last 20 years, on a 3-yr smoothed (moving avg.) basis. Additionally, we specify the percent of sales weighted innovation represented by each ATC for both BMY and its peer group

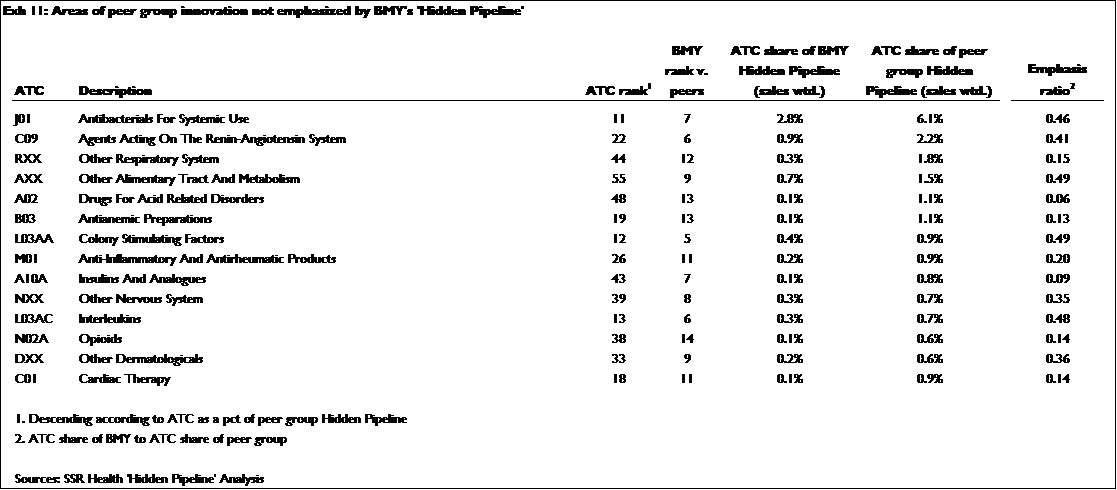

Exhibit 10 shows where BMY ‘is’; conversely Exhibit 11 shows where BMY ‘is not’. The 14 research areas (ATCs) for which BMY has an emphasis ratio < 0.5 are listed, as are these ATCs’ rank both among the broader peer group and within BMY, and the percent of quality- and sales-weighted innovation in each ATC for both the broader peer group and BMY

[1] The companies do not follow consistent patterns of pre-phase III pipeline disclosure through traditional information channels (e.g. SEC disclosures, investor meetings, press); some companies provide much more detail than others, and the amount of detail provided by any given company can change over time. In few if any cases do companies disclose the percentage of total pre-phase III activity that is represented by projects on which detail is given. In the case of patents, we believe the companies’ pre-phase III (but not phase III and after) behaviors are both consistent and thorough – meaning the companies all behave similarly; and also meaning that all companies disclose (i.e. patent) the great majority of pre-phase III projects that show any significant level of commercial promise

[2] We work with US patents only. At least since the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PERCENT), patent filings for larger, multi-national research-based organizations have become global – thus we believe adding ex-US patents to our datasets would add little or no useful signal

[3] Our method of quality weighting relies on several variables, including in particular citation patterns (e.g. number of citations and rate of citation accumulation) and patent ‘vintage’. Raw (unweighted) patent counts have very limited relevance

[4] Specifically, we categorize patents according to the World Health Organization’s ATC (Anatomic, Therapeutic, Chemical) classification scheme

[5] Essentially enterprise value less the present value of all products / projects / lines of business other than projects in phase II and earlier development

[6] We recognize there are two limits of our method which emerge when analyzing smaller companies. First, the most fundamental premise of the ‘Hidden Pipeline’ is that it is in fact hidden. In the case of very large companies, the assumption that pre-phase III pipelines are in fact hidden is robust; however the quality of this assumption deteriorates as companies become smaller. Smaller companies will have fewer pre-phase III projects, making it more practically feasible for investors to identify and assess these – making them more comparable to the assets we define as ‘tangible’. Second, our method relies on an assumption of central tendency – i.e. that a large portfolio of projects in a given set of therapeutic areas and with a given overall quality-adjusted patent count will have a similar economic value to a comparable large portfolio of the same therapeutic area mix and overall quality-adjusted count. This assumption is robust with large portfolios – especially since the larger companies have such tremendous overlap in terms of diseases (and disease mechanisms) pursued. However the assumption is weaker with small portfolios. Smaller companies A and B may be in similar therapeutic areas with similar quality-adjusted patent counts, but could be working on highly distinct approaches

[7] Based on arbitrarily defining overvalued as having a ratio of innovation : value ≥2

[8] Based on arbitrarily defining undervalued as having a ratio of innovation: value ≤ 0.50

[9] In reality we’re very aware that ‘Hidden Pipelines’ with similar therapeutic area mix and quality-adjusted ‘weight’ of total innovation will have different economic values. However, we argue that when these pipelines are ‘hidden’ that the market has no factual basis (other than quality-adjusted patents and therapeutic area sales weighting – which we don’t believe the market uses) on which to assign the pipelines different values – and that the market’s assignment of different economic values reflects nothing other than the market’s inability to efficiently value intangibles. Thus over time, the most reasonable guess as to the relative values of two pipelines of identical therapeutic area mix and quality-adjusted volume of innovation is that the two pipelines have identical values

[10] We count those patents making claims relevant to biomedicine

[11] Here again the limits of our method as companies become smaller should be kept in mind – please see footnote 6